Imagine the scene, one that’s becoming more common every day. A product manager, empowered by the latest AI tools, has built a stunningly realistic proof-of-concept for a new feature in just a few hours. The prototype is slick, functional, and gets the entire business buzzing with excitement. The path forward seems obvious and fast.

The energy in the planning meeting is electric, filled with optimism—until the engineering lead presents their estimate to build the production-ready version: three months.

The excitement in the room instantly evaporates, replaced by a thick, heavy silence. You can feel the air crackle with unspoken questions and accusations. The product team, who saw a working model come to life in an afternoon, feels a hot mix of frustration and suspicion. “Why is this so hard? We’ve already built it. Are the engineers just being difficult? Are they gold-plating this?”

The engineers, in turn, feel a familiar wave of defensiveness and exhaustion. They see the iceberg hidden beneath the tip of the AI-generated prototype—the need for security, scalability, testing, and integration with a dozen brittle, legacy systems. They think, “They don’t understand the complexity. They think this is a simple copy-paste job. They don’t see the price we pay for every shortcut we’ve ever taken.”

The inevitable, unsatisfying explanation surfaces, a two-word ghost that haunts every planning meeting: “…well, it’s because of technical debt.”

We all know this story. We accept technical debt like bad weather; we complain about it, but we rarely understand its true nature. If everyone in the organisation agrees it’s a problem, why does it only ever get worse?

The answer is that we’ve been diagnosing the wrong disease.

It’s Not a Mess; It’s a Mortgage

So, what explains the chasm between a three-hour AI prototype and a three-month production estimate? The answer lies in the invisible structure of our existing systems. The AI prototype was built on fresh, open land. The real feature must be built in a city already full of skyscrapers, aging infrastructure, and a complex network of roads—all financed by a hefty mortgage.

Our first mistake is treating this technical debt as a sign of engineering failure. It’s not. In fact, not all debt is bad. Like a financial mortgage used to buy a house, some debt is a strategic tool—a loan deliberately taken out to achieve a critical business goal, like being the first to market. The goal isn’t zero debt, which is an impossible and likely undesirable state for any growing company. The goal is to manage it wisely.

This is where we must reframe the conversation entirely. Technical debt is a misnomer; it’s Business Debt with a technical-sounding name. It’s Product Debt. It’s a risk management problem that belongs to the entire organisation. It was created by a series of past decisions—some made by engineering, some by product, some by the business—all in the service of speed and growth. It’s not their technical debt; it’s our business debt. A “WE” problem, not a “THEM” problem.

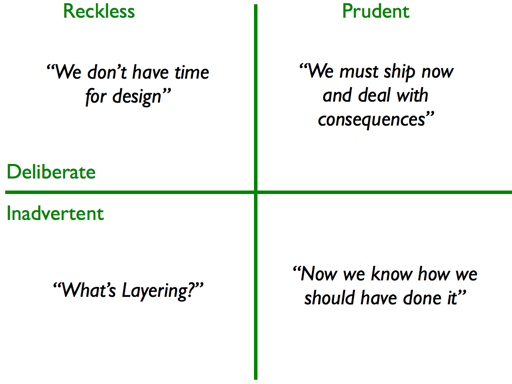

To manage it, we first need a shared language to describe what kind of debt we have. Martin Fowler provides a brilliant diagnostic tool with his Technical Debt Quadrant, which splits debt into two axes: Prudent vs. Reckless and Deliberate vs. Inadvertent. This framework allows the entire leadership team—not just engineers—to shift the conversation from blame to a strategic assessment of our past decisions. It helps us ask: “Was this a strategic loan we took on with our eyes open, or was it simply the result of carelessness?”

The Technical Debt Quadrant

When the engineering team gives their three-month estimate, they are accounting for debt that likely falls into all four quadrants:

Prudent and Deliberate: This is the “good” debt. The team might have previously decided, “We’ll use a simpler, less scalable database for now to get the last big feature out before our competitor. We accept we’ll have to replace it next quarter.” This was a conscious, strategic trade-off made with the business to seize an opportunity. The key question here is one of communication: Did the engineering team make the future repayment clear? Did the business consciously accept the risk? Too often, engineers keep quiet, turning a prudent choice into a future surprise.

Reckless and Deliberate: This is the debt everyone knows we shouldn’t be taking on. It’s the pressure-induced decision to say, “We know we should be writing automated tests for this, but the deadline is impossible, so we’re skipping them all just to get it shipped.”

Prudent and Inadvertent: This happens when the team learns more over time. For example, “When we first built this service two years ago, this was the best way to do it. Now, we’ve learned a much better, more efficient design pattern. Our original design wasn’t wrong, but it has now inadvertently become debt we need to address.”. We often only learn how we should have built a system a year after we’ve already built it.

Reckless and Inadvertent: The most dangerous quadrant. This is the classic “We had no idea what we were doing”. The initial AI prototype, if simply copied into production, would be a perfect example of this. A product manager, unfamiliar with production systems, might inadvertently build a prototype that is insecure, unscalable, and impossible to maintain. Also, because companies are pushing for AI empowered or AI driven features at a rapid rate, we are very likely to see a major surge of this type of technical debt very soon, if it hasn’t started to surface already in many organisations.

Once we understand the loan, we must understand the interest payments. The interest on our business debt isn’t an abstract concept; it’s paid daily.

The interest payments are paid in Paper cuts

Drawing from Jeff Bezos’ concept of customer friction, the interest on our debt is paid through thousands of tiny, morale-killing “Paper Cuts”. I will just straight steal this concept from Jeff and apply it to engineering and the DevEx (a topic for another day) as it applies perfectly well.

These paper cuts aren’t catastrophic failures; they are the small, daily points of friction that plague an engineering team. A slow build process that adds five minutes of dead time to every small change. A confusingly named variable that forces every new developer to spend an hour trying to understand its purpose. A poorly documented internal API that requires a “quick question” on Slack, breaking another developer’s focus. A flaky test that fails randomly, forcing the team to run the entire test suite again, wasting valuable time and eroding trust in their own safety net.

Individually, each of these paper cuts seems trivial—a minor annoyance. But collectively, they are the reason it takes six weeks to do what should be like a two-week job. These are not just an engineering problem. When a developer is slowed down by these cuts, that’s a direct tax on the product roadmap. When a bug takes twice as long to fix because the system is a tangled mess, that’s a direct hit to customer satisfaction and the support team’s workload. These paper cuts are how the debt makes itself known, causing the entire organisation to bleed efficiency, enthusiasm, and ultimately, its ability to compete.

The Political Reality

This brings us to the core of the problem. The reason we fail to manage technical debt is that we treat it as an engineering problem. In reality, it is a political problem.

What does that mean? In most organisations, an invisible wall exists between “The Business” and “Engineering”. When a customer-facing bug appears, it’s an “all hands on deck” situation; it’s a Product problem, and therefore a WE problem. Everyone understands the impact, and resources are mobilized. But technical debt is different. It’s perceived as a mess happening inside the engineering black box. It becomes a THEM problem. The business and product teams see only the symptom—slowing delivery—and often conclude that engineering is the sole cause and should be the sole owner of the solution.

Engineers, in turn, often reinforce this isolation. We retreat behind a wall of jargon, failing to translate the intricacies of a brittle system into the language of business risk. We might adopt a gatekeeping attitude, frustrated that others “just don’t get it.” We inadvertently accept the narrative that the health of the codebase is our problem alone.

But the real accountability lies with leadership—on all sides. Product leaders who consistently push for new features without budgeting for the health of the system are actively creating Reckless technical debt. They are, in effect, taking out high-interest loans on behalf of the entire company without a plan to repay them.

Equally accountable are the silent and conforming engineering leaders. When we fail to act like business owners, we compound the problem. An engineering leader who sees their job as simply taking orders and delivering features, without pushing back and advocating for the long-term viability of the technology, is failing in their primary duty. We are not just here to write code; we are here to steward the technical assets that power the entire business.

This is where politics, in its truest sense, becomes essential. In this context, “politics” is not a negative word. It is the essential leadership skill of influence, negotiation, and building consensus to allocate limited resources to what is truly important. To solve the technical debt crisis, engineering leaders must step out of their black box, learn to speak the language of the business, and master this game. They are asked to win a game they are not being taught how to play.

The Leader’s Toolkit: From Political Problem to Shared Accountability

To solve this problem effectively and ethically, leaders must equip their entire organisation with a toolkit for translating technical reality into business impact. This isn’t about “winning” a game against other departments; it’s about building the systems and shared language necessary for the entire business to win together. These tools are for building bridges, not for fighting battles.

1. Create a Shared Language: It’s Just “Debt”

The first and most critical step is to change the language.

Stop calling it “Technical Debt”: From this moment on, it is simply “Debt.” This simple change is a powerful political act. It removes the implicit and incorrect assumption that it is solely engineering’s problem and reframes it as a shared business liability.

Align your engineering team: Coach your engineers to stop talking about debt as a list of personal complaints. Instead, they must learn to present it as a risk register that impacts the entire business. Every conversation about debt should be grounded in its effect on delivery, stability, or security.

2. Build a System for Visibility and Prioritisation

You cannot manage what you do not measure. The next step is to make the debt visible and manageable for everyone.

Maintain a Debt Backlog: Just as you have a product backlog, you must maintain a debt backlog. This is a living document, owned by the engineering team but visible to product and the wider business.

Score Each Item: For every item in the backlog, create a simple score for Effort (how hard is it to fix?) and Impact (how much pain does it cause in the form of “paper cuts”?). This creates a data-driven score that helps remove emotion from prioritisation.

Use a Venn Diagram for Alignment: Create a visual model where one circle represents your Product Roadmap and the other represents your Debt Backlog. The intersection is where the magic happens. This is the debt that, if fixed, will directly accelerate a key roadmap initiative, and subsequent initiatives in the future. This becomes the shared priority and the easiest place to get consensus. Keep in mind some debt is focused on specific parts of your system, while other debt creates ripple effects in your entire engineering department. Ensure you identify those proactively.

3. Quantify the Cost of Inaction with Hard Numbers

Leaders can’t act on “the code feels messy,” but they can and will act on clear, data-driven evidence.

Use DORA Metrics as Your Dashboard: These four key metrics are the language of leadership for delivery performance. Use them to tell a story:

Lead Time for Changes: “Our lead time to get a simple change to production has increased from 2 days to 10 days in the last year. This is a direct consequence of the debt in our automated test suite. Every change we make requires a massive amount of manual testing because we are not spending time in automated tests.”

Change Failure Rate: “Our failure rate for deployments is now 25%, meaning one in four of our attempts to deliver value fails. This is because our testing environments are unreliable due to unmanaged debt.”

Deployment Frequency: “We used to be able to deploy multiple times a day; now we struggle to deploy weekly. This debt is costing us the majority of our opportunities to innovate and respond to the market.”

Time to Restore Service: “When we have an outage, it now takes us, on average, three hours to recover, up from 20 minutes last year. The complexity debt in our core systems is creating a direct and unacceptable risk to our customers.”

Not only can you measure how your development experience is deteriorating, but now you can realistically even set new targets to achieve productivity in the future. You can even now move from reactively managing “debt” and its risks, to also pursue higher productivity and faster development cycles. You can turn this around from “managing” to “leading”. Perhaps even have a roadmap shared with product on large debt topics that can help our business win more at the market.

4. Integrate Debt Repayment into Your Workflow

Repaying debt must become a regular, predictable part of how you work, not a special occasion.

Schedule “Fix-it” Sprints or Hackathons: For larger, more complex debt, dedicate time. Get support from product and the business by framing it as an “Innovation Accelerator” event. The goal isn’t just to “clean up code”; it’s to “buy back our future speed.”

Add “Quick Wins” to Sprints: For smaller debt items (the paper cuts), empower your team to pull them into sprints as stretch goals or as part of their allocated time for improvements. This builds momentum and a continuous improvement culture.

5. Frame the Foundational Risks

Finally, some debt isn’t a matter of speed or efficiency; it’s a matter of survival.

Identify Non-Negotiable Risks: Security and compliance issues are not a “trump card” to be played in a negotiation; they are foundational risks. This is the debt that can put the entire business in jeopardy.

Speak in Terms of Business Impact: Frame it clearly: “Using this out-of-support library isn’t a technical choice; it’s a business decision that puts our ISO certification at risk, which could cost us our three biggest clients.” This reframes the conversation from “we should” to “we must.”

The Resolution: The Innovation Tax

If we fail to master these political skills, we are left with the brutal consequences of inaction. Unmanaged debt imposes a hidden “Innovation Tax” on all future work. Before your teams can build any new feature, they must first pay this tax in the form of extra time, complexity, and frustration while wrestling with the brittle systems of the past.

But here is the critical truth: this tax compounds. And while your organisation is busy paying it, your competitors are not. Every hour your team loses to friction is an hour your competition invests in innovation. Every talented engineer who leaves in frustration is one your competition can hire. Left unpaid, this debt doesn’t just slow you down; it creates a competitive disadvantage that can become insurmountable.

Your role as a leader is to make this tax visible. But more than that, it is to understand that managing debt is not a technical task to be delegated—it is a core leadership responsibility. It is a choice about the future you are building and the standards you are willing to accept.

The conversation about debt is never easy. It requires courage. It requires you to act not just as an engineer, but as a politician, a negotiator, and a business owner. But the silence is always more expensive than the conversation will ever be.

The real question is not whether your organisation has debt. Every organisation does.

The real question is: Have you created a culture of true ownership, where everyone—Product, Engineering, and the Business—understands that the debt, like the success, belongs to all of you?